The Toilet Bowl of Life

The Toilet Bowl of Life

Back in the previous century, my friend, John, and I labored together in the sweatshop of a local electronics manufacturer. As often happens, shared adversity created a bond of friendship which still remains 45 years later.

John is an engineer. While it might be more proper to say John “was” and engineer since he’s even older than me and long-retired, I tend to think, “once an engineer, always an engineer”. That’s because by its very nature, John’s brain operates differently than mine.

Whereas my “creative” brain operates more like a water balloon exploding onto the picnic table of a family outing, John’s brain operates in a far more focused nature — more like the water hose nozzle used to clean up the aftermath of that riotously interrupted repast.

The age-old argument is whether John’s brain is the way it is due to nature (DNA) or nurture (his parent’s example). Either way, John passed his analytical curiosity on to one of his young boys and this story provides evidence of both influences.

When John’s son (who shall remain unnamed) was only three or four years old, he began to exhibit those analytical interests with regards to the family toilet. A toilet is a wonderful invention. You simply fill it with all the stinky refuse of life, push down that shiny chrome handle and the inconvenient elements of your experience are whisked away.

Like many toddlers, John’s son became obsessed with that whirlpool miracle and its ability to “disappear” stuff, so he began to experiment — initially with extra toilet paper and later with defenseless toys of ever-increasing size and solidity.

While John’s son had inherited his father’s analytical learning style, he lacked his father’s years of experience and subsequent foresight. Like all meaningful experience, John’s son learned from his mistakes, and his immediate mistake was irreparably clogging the family toilet, an error that resulted in a malodorous mess.

A normal thinker like myself would simply meet that challenge by swearing loudly and kicking the toilet, followed by an apology to his wife and child who had just witnessed the outburst, and further followed by a call to the local plumber. But my friend, John is not like me; he is an engineer. Consequently, he set about righting the wrong himself.

Now, I don’t know about you, but my personal theology contends that, of all the things God gave man to do in this lifetime, plumbing is penance for the worst kind of offense. Having been forced to undertake the toilet-rehab task on more than one occasion, I can assure you that removing those two chrome nuts and lifting that pristine toilet off the clean tile floor will not result in a pleasurable experience.

But John was an engineer, so he did just that — and encountered the matchless hideousity of that foul demon which lies entrapped just beneath the sparkling white ceramic. After overcoming his initial revulsion and dealing with the excess water contained in the toilet, John turned the offending instrument on its side and peered up into its innards — another task unintended for the faint of heart.

In short order, John diagnosed the problem as a couple of insoluble toys lodged within the path of banishment (the toilet’s p-trap). The next problem was that John’s adult hand, even though willing to enter that foul dungeon of excrement and dislodge the errant toys, was simply too large. Enter John’s young son with smaller hands and weaker stomach but more important, a weaker will than John’s.

Through much coaxing and parental manipulation — which might land John in prison amidst today’s woke parenting culture — John convinced his son to live up to the consequences of his errant actions and retrieve his soiled toys. I’ve met John’s son, now in mid-life, and can attest that he suffered no debilitating psychological issues from that event (apart from perhaps an obsession with hand washing) but John assures me that he never flushed another toy down the family toilet.

So, what’s the point?

Sometimes we have to get our hands dirty, cleaning up our own messes, rather that throwing money (or votes) at them in order for someone else to fix the problem. And perhaps it’s precisely our repulsion at the consequences of our irresponsibility that instills us with the motivation to do better next time. Shit happens but it doesn’t have to keep happening.

Imagine an entire generation of people secure in the fact that they are loved for who they are rather than what they’ve done (or failed to do). Those folks would have the confidence to own and address the consequences of their misdeeds — consequences to themselves as well as to others. They would no longer need to balance guilt with blame, and they would no longer need to judge others in order to assuage their own feelings of inadequacy.

Let’s talk. I’d really like to hear what you have to say, and it might even give me something to write about. Email me at guy@lawsoncomm.com.

Let’s talk. I’d really like to hear what you have to say, and it might even give me something to write about. Email me at guy@lawsoncomm.com.

I’ll buy you coffee and we can compare notes. I promise not to steal your ideas without permission.

![]()

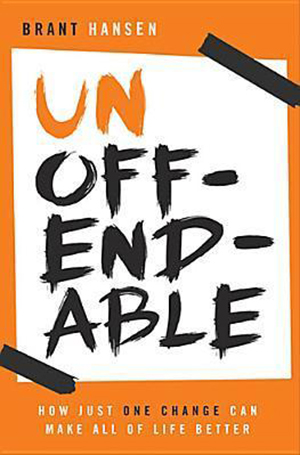

When you’re living in the reality of the forgiveness you’ve been extended, you just don’t get angry with others easily. I suspect our sense of entitlement to anger is directly proportional to our perception of our own relative innocence.

When you’re living in the reality of the forgiveness you’ve been extended, you just don’t get angry with others easily. I suspect our sense of entitlement to anger is directly proportional to our perception of our own relative innocence.

― Brant Hansen

Did someone forward this newsletter to you after reading it themselves? Don’t settle for that!

CLICK HERE

to get a fresh, unused copy of this newsletter sent directly to you every Sunday morning. If you decide it stinks, you can always unsubscribe.

Unoffendable

— Brant Hansen

I’ve read a lot of books in the last few years but this one just keeps coming back around for a reread. Maybe its just because he has such a great attitude about life and his fellow human beings but perhaps because he’s hit on a facet of absolute truth that is essential to understanding our place in the universe.

A meeting of great minds who think alike