“Us”

“Us”

In 1962, I was in the second grade at Edith Beaver Elementary School. Every morning, my older brother, Bill, and I would trudge to the breakfast table and choke down the dreaded Oatmeal and toast (Oatmeal still makes me nauseous to this day). Then, we’d pull on our blue jeans, roll up the cuffs, mount our new Western Flyer bicycles, and traverse the roughly half mile to our school.

At school, we parked our bikes in the massive bike racks alongside at least 150 other bikes. There were new bikes, old bikes, girl’s bikes, boy’s bikes, bikes with baskets, bikes without fenders, and even some of those expensive Schwinn bikes. Nobody ever locked their bike because every kid knew what their bike looked like and there was no concern about anyone taking the wrong bike.

I knew every one of the 25 kids in my second-grade classroom as well as the kids in the other two second-grade classes. I even knew most of the kids in third grade and a few in my brother’s fifth grade classes. We were all alike — white middle-class kids from similar families in a small North Texas town.

It would be a couple more years before I discovered that my hometown was also home to a large black community that was nothing like mine. Interestingly, the public schools had maintained a boundary between our cultures, and it would be years before I became friends with folks from that other half of my own home town.

My mental picture of the world at that time was a vast network of small towns just like mine, filled with kids just like me, who had families just like mine, and maybe even rode red, Western Flyer bicycles.

Omens

Early that school year, every student received a stainless-steel I.D. bracelet with our name, address, phone number and blood type on them. They were cool so we all wore them without giving it a second thought. Then, we began practicing “tornado” drills where everyone in the school went into the halls and knelt on the floor next to a wall.

It wasn’t until one of my high-school-aged sisters mentioned atomic bombs at the dinner table, eliciting a serious stink-eye from my mother, that I began to suspect something more than tornados was afoot. Then, one evening when I’d been told to play in my room, I wandered out to the kitchen in search of a glass of water, only to find both my parents glued to our old Philco black and white TV while a serious looking newscaster talked about naval blockades and missiles.

At the time, my vocabulary didn’t include the word “preposterous” but that was the phrase my eight-year-old mind was searching for. The idea that a bunch of ignorant natives on an island in the Gulf of Mexico could somehow shoot a missile with an atomic bomb all the way to the United States, had to be a joke.

After all, we were the most powerful nation on the globe and our army was led by a handsome and intelligent president who had been a war hero himself. A year later, that larger-than-life president would encounter eternity, but in 1962, he was the most powerful man alive.

That was the first time I began to think about “them” — those other people who didn’t look like us, dress like us, or think like us and who maybe even wanted us dead. They had to be someone God hated.

Years later, when I began attending Garland High School, I realized we had a “them” that was even closer at hand, the dreaded South Garland High School. As the only other high school in town at that time, they were the filthy vermin who opposed us on the football field and even spray painted their school mascot’s name on my high school’s sidewalk. They were children of the antichrist.

It was a case of “Us” versus “Them”.

Today, it’s impossible to count the “us” and “them” categories — college alumni, political parties, race, religion, sexuality, and pro sports enthusiasts, not to mention those dreaded Russians, Chinese Commies, and Middle-East terrorists.

Why is it that “they” are always assumed to be lesser, or even evil, human beings? When is the last time you heard someone say, “Those people are great. I want to be just like them.”? Could it be that deep in our souls, we know something is amiss in our own lives and we need to feel that at least we’re not as bad as “them”? What the Hell happened to “Us”? Are we nothing but the sum of our experiences? …or is there more?

Let’s talk. I’d really like to hear what you have to say, and it might even give me something to write about. Email me at guy@lawsoncomm.com.

Let’s talk. I’d really like to hear what you have to say, and it might even give me something to write about. Email me at guy@lawsoncomm.com.

I’ll buy you coffee and we can compare notes. I promise not to steal your ideas without permission.

![]()

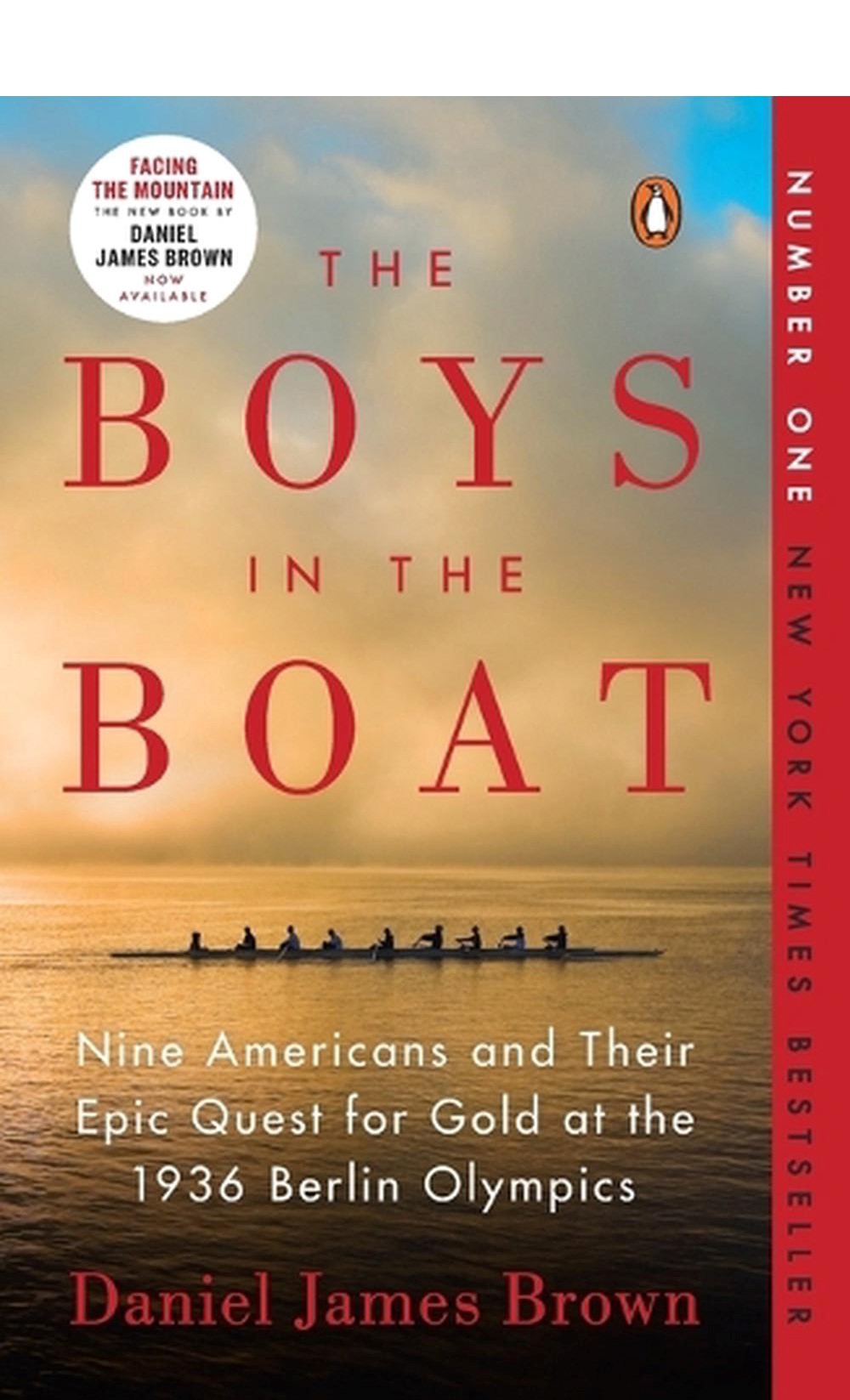

All were merged into one smoothly working machine; they were, in fact, a poem of motion, a symphony of swinging blades.

― Daniel James Brown,

The Boys in the Boat

Did someone forward this newsletter to you after reading it themselves? Don’t settle for that!

CLICK HERE

to get a fresh, unused copy of this newsletter sent directly to you every Sunday morning. If you decide it stinks, you can always unsubscribe.

The Boys in the Boat

— Daniel James Brown

If you saw the recent movie based on this book, you know absolutely nothing about the incredible story of personal growth and mutual respect that Brown crafted. Like everything else Hollywood touches, they perverted it to fit their own agenda. Read “The Boys in the Boat” and you’ll gain a whole new perspective on unity. Thanks to my friend, Paul Mayer, who introduced me to this book four years ago. And thanks to our mutual friend, Fritz Heinke, who introduced Paul to it years before that.

A meeting of great minds who think alike