Another Insane Concoction

Nope. This is not whiskey-inspired prose. It’s a rational analysis of the most common one-two punch to our success. Just like foolishly mixing household cleaners, we all suffer from the combination of two otherwise semi-benign practices — unrealistic goals and left-over teenage rebellion. Read on and you’ll realize that I’m not suffering from mind-altering ingestives like you originally perceived (yeah, you’re right; I did just make that word up but you knew what it meant and it’s derived from legitimate Latin roots, so there ya go).

The Eighty Percent Rule

When I was in college back in the previous century, I had a business professor who used to say, “It’s better to shoot for the moon and only get ten feet high than to shoot for the streetlight and never leave the ground.” At the time, I thought the man was a genius and I even repeated his favorite quote on several occasions. Now, I understand he was an idiot and his idiocy embedded itself in my psyche with lasting damage. Fortunately, I mostly quoted him at parties, attendees of which are now too burnt out and/or senile to even remember the party, much less the numbskull who recited that ridiculous adage. But the damage to my judgement still routinely rears it’s ugly head in the form of unrealistic expectations (“Sure, she’s not perfect but after we’ve dated for a while, I’ll convince her to change”). Moreover, I don’t even have the dedication to meet my goals one-hundred percent (“I’ll shoot for making $10,000 on this deal but be happy with $8,000”). Why can we not just set realistic goals and do whatever it takes (including “hair-lipping the Pope”, as a person I know likes to say) to meet or exceed those goals? Moreover, how did we ever let the “80%” mindset become ingrained in both our personal and our cultural thinking?

OK, put your finger there and let’s move on. If poor goal setting is the bleach, let’s explore the ammonia.

Teenage rebellion

When I was an all-knowing adolescent, I determined, just like you did, to never turn out like my parents. My parents were cheapskates, and skinflints, and penny-pinchers. My friends had new Schwinn Stingray bicycles while I was still riding a five-year-old Western Flyer with giant tires, a tiny seat, and rusty fenders. My friends got drum sets for Christmas while I got new school clothes. In general, my parents were about the worst parents an infinitely wise kid could imagine. I WAS NEVER GOING TO BE LIKE THEM!!

In all fairness, it’s important to note that my father grew up in an orphanage and my mother grew up on an Oklahoma sharecropper farm during the great depression. There was good reason for their lack of frivolity when it came to spending but my youthful intellectual prowess blotted that part out. In addition, their tight-fistedness, was a fundamental influence in me securing my first paper route (and regular paycheck) at the age of nine. I knew if I wanted something, it was up to me to earn it because nobody was going to give it to me (even as a reward for being the perfect son).

What I didn’t realize, as I was repeating my mantra of independence over and over and over, was that like a tree bore, it was rooting it’s way deeper and deeper into my character and laying eggs along the way. Even today, when I look in the mirror, I see a middle-aged man who is still, in many ways, rebelling against his parents. That’s so much a part of who I am that even my friends can see it. I know they can see it because I recognize exactly the same thing in them so they must surely see it in me. “Takes one to know one”, as we used to say.

Mixing the Poisonous Concoction

Now, move back up to that earlier thought you were keeping your finger on. If we set goals that we never subconsciously intend to fully meet, and if, in our innermost thoughts, our ultimate goal is to not be like our parents, where does that leave us? Unfortunately, at least in my case, it does not always leave us with the best 20% of our parents; we get stuck with the parts we really didn’t need (yeah, our parents were not perfect people). For me, it resulted in a love-hate relationship with money. I’m always chasing it but when I get it, I spend it extravagantly lest I be thought of as a penny-pincher like my parents were. For many of my friends, the result is an irrational disdain for anything similar to their parents’ beliefs — that even goes for the friends who got the Stingray bikes and drums.

Now, I’ll admit that there are about five percent of you who are legitimately shouting “BS” at this point because you’re among those nerds who grew up idolizing their parents. I’ll get to you later but for now, the question (for both us “regular” people and you suck-up nerds) is, “How old do we have to be before we just let go and become ourselves rather than reacting to (or mimicking) our parents?” And, when do we start setting achievable goals based on an accurate assessment of who we really are?

Maybe you think I’m just trying to provoke you into hitting “reply” and starting a conversation. You’d only be half right but why not have coffee with me and convince me why I’m at least half wrong? Your move.

The single most destructive personality trait I’ve seen in friends, enemies, society in general, and especially in myself, is a tendency towards an over-inflated sense of self-worth. It was not low self-esteem that led Bernie Madoff to steal millions from investors, nor is it low self-esteem that prompts the neighborhood thug to pull a gun and carjack an innocent motorist, nor is it low self-esteem that prompts cancel-culture warriors to wage war on a local small business just because the owner’s car is sporting an unpopular bumper sticker.

We’ve abandoned the rational thinking of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle (as well as the objectivity of every successful scientist of the last 20 centuries). We’ve replaced that reasoning with emotionalism and consensus-based truth that hinges on ego rather than outward-focused investigation. Today, anyone who fails to see things the way our highly esteemed herd sees them is a God-forsaken imbecile who must be silenced, rather than an intelligent human being who happens to see things from an alternate perspective. If the last two years of COVID madness have proved anything, they’ve proved that covering our ears and silencing alternate views only compounds the potentially disastrous effects of any serious situation.

Would we not be better off — both in our personal and business lives — to get up every morning and return to Paul’s simple advice so that we might “think so as to have sound judgement”? What if we started every day by asking ourselves, “What’s the most serious personal or business problem I need to solve today?” Once we’ve set our ego aside and put our finger on the problem, should we not then ask ourselves, “Who can I go to for advice or at least a different point of view on this issue?” I’m not talking about dumping our problems on someone else. I’m talking about asking a trusted friend for their views about how we might best attack pressing issues. They might just see things that we haven’t yet seen and we might just learn the most important lesson of all — that everything we know is not everything we need to know.

Warren Bennis, in his short publication, “The Power of Truth,” tells how Lee Iacocca, in his days at Chrysler, would randomly appoint a “contrarian” to attend policy meetings and point out everything that was wrong with the plan of the day. This was not done in jest. It was serious criticism, mounted by intelligent and knowledgeable upper management staff with specific instructions to identify and emphasize any possible shortcomings they could find – especially if their analysis diverged from Iacoca’s. Imagine giving a trusted mentor that kind permission with our dreams and schemes. Now, imagine that we swallowed our pride and actually listened to them.

If you still think I’m blowing smoke, you can close those shudders now — or, we could sit down and talk so you could introduce me to a different perspective. You know where the reply button is.

“Children begin by loving their parents; as they grow older they judge them; sometimes they forgive them”.

― Oscar Wilde

“To forgive is to set a prisoner free and discover that the prisoner was you.”

― Lewis B. Smedes

Great Reads (or Listens)

Seven More Men

Eric Metaxas

This guy is rapidly becoming my favorite author. It’s no surprise that he’s good buds with Oz Guinness, my other nearly favorite author. In this book, Metaxas provides compelling biographies of Martin Luther, George Whitefield, William Booth, George Washington Carver, Sergeant Alvin York, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, and reverend Billy Graham.

Fish Out of Water

Eric Metaxas

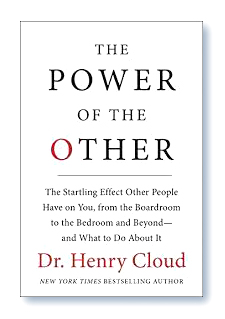

I warned you he was quickly becoming my favorite writer. This is the story of how a really great writer became, well, a really great writer. It’s also about his search for meaning in a society where meaning is the last thing most people are searching for – coming in a distant last after the hottest mate, the biggest house, the hottest car, and the biggest bank account (and maybe the solution to Rubik’s cube).